In early April, the president of the European Commission, Jose Manuel Barroso, announced during a conference in Brussels an EU declaration recognizing five of the most important sacred places in the Mediterranean region. Alongside Mecca, Jerusalem, Mount Athos and the Vatican, there are also the Serbian Orthodox monasteries in Kosovo.

The president stressed that special protection had to be in-place for the protection of the monasteries, which should be centres of inter-cultural dialogue rather than a focus for conflict.

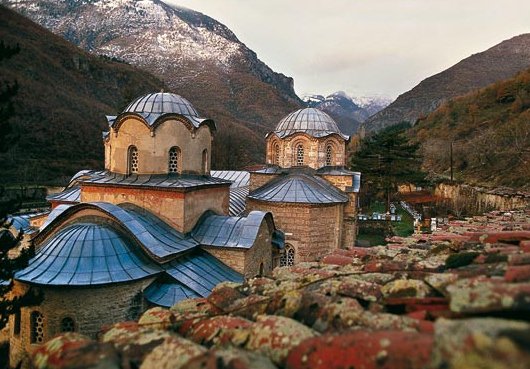

The significant monasteries are Gračanica, in a Serb enclave near Pristina, the ancient Patriarchate at Peć and the Monastery at Dečani. Both are of huge symbolic importance for Serbia; as a Serbian Orthodox Bishop once told me, “if these Monasteries were destroyed, Serbia would no longer exist.” These monasteries and others – south of the river Ibar – are surrounded by Kosovo Albanians. Now there are very few Kosovo Serbs living in the small towns of Dečani and Peć. They stand alone, reminding me of St Catherine’s Sinai.

The EU declaration made particular reference to the need for security for the shrines in Jerusalem and for Serbian Orthodox monasteries. It was right to do so. Meeting many Kosovo politicians during the last election campaign I was struck by the unanimity; ‘these monasteries are Kosovo monasteries. They are not Serbian. The monks and nuns can stay there, but they have to recognise these are Kosovo Orthodox monasteries’. Such views are strongly endorsed by the veterans of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) and the Self Determination movement (Vetëvendosje) led by Albin Kurti.

No one should underestimate the hold these organisations have on shaping public opinion.

The Serbian Orthodox Church demands the monasteries and churches be given special status; some would argue they need to have extraterritorial status like the Swiss Guard at the Vatican.

The Monks at Dečani have recently been the target of abuse from local young Kosovo Albanians; graffiti appeared on the walls of the monastery.

The tension between monastery and municipality is aggravated by legal disputes, and threats about the development of the land by the monastery since 1999. There has been no progress in resolving these matters.

So what is to be done? The Serbian Orthodox Church and the Kosovo Albanians have to sit round the table. It is not possible or desirable for either the monasteries or the municipalities to take refuge by complaining to UNMIK, EULEX, the OSCE or whatever combination of international organisations. There is a limit to what internationals can do; and as their record since 1999 show, they have done very little.

There has to be face-to-face meetings – carefully prepared as part of track two diplomacy. Only in this way can there be any progress. It was Nelson Mandela who said, “if you want to make peace, do not speak with your friends, speak to your enemies so they become partners”. (And it is worth noting that there is no funding available for peacebuilding from the European Commission).

Therefore a peace process needs to come into being where slowly and patiently these issues are addressed.

Once there has been some agreement to participate in a peacebuilding process, then the demonising of both parties has to stop. The sort of language which refers to Dečani as a ‘fascist monastery’ is dangerous and untrue. Those who describe the monasteries in this way have never sat with the Monks. And one thing the Kosovo government needs to do is to publicly disassociate itself from this sordid rhetoric.

The Serbian Orthodox Church, for its part, should understand how strange their monasteries appear. Islam has no tradition of Monasticism, so the Serbian Orthodox Church should create educational programmes designed to explain the reasons for the existence of monasteries, why monks and nuns are unmarried and take vows of poverty and obedience.

Many in the international community also need to become more literate religiously – whatever their personal views. Dečani and Peć are not just museums; they are places committed to worshipping God.

As Kosovo Albanians begin to understand the reason for the monastic life, much of the prejudice and fear which is based on ignorance will slowly evaporate.

The Orthodox monasteries and the municipalities of Peć and Dečani have to start creating the basis for healthy community relations. There is no other alternative. The Soul of Europe is ready to help facilitate this process. When this begins to happen, Kosovo can really declare what is written in its constitution – that minorities are welcome.

Many governments withholding recognition will begin to change their minds. Serbs living in these monasteries and elsewhere south of the river Ibar will no longer feel abandoned and under constant threat. Even tourism in Peć and Dečani could benefit the local economy, as these holy sites become what the Declaration said they should be – places of intercultural dialogue.

Reverend Donald Reeves MBE is the founder of the Soul of Europe. The Soul of Europe works as catalysts and mediators to ensure a peaceful resolution to conflicts, particularly in the Balkans.

Reverend Donald Reeves MBE