The suffering of Egypt’s Christians is there for all to see — their churches have come under attack and people have died — but not the perpetrators.

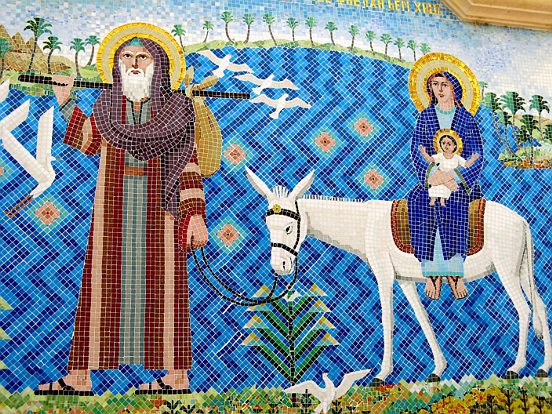

Overlooking the Nile, St Mary Church in the modern Maadi suburb of Cairo held a prayer for all Christian martyrs of the past year. Attendees tried to find comfort in the colourful mosaic of Virgin Mary.

“We trust God. If God said, ‘Blessed be Egypt, my people’, then we know that we will definitely head somewhere good. It has been a difficult year for us — it began with the bombing of the Two Saints Church, continued with the killing of our innocent sons and burning of churches. No one was punished” said Isis Fouad, an elderly Coptic lady.

Joined by hundreds, Fouad lit a candle and prayed, in the church which falls on the “Holy Family Trip” route. “We aspired for a better living after the revolution; we hoped things would change for the better,” Fouad was in tears as she spoke to Weekend Review.

The Coptic Christians, who make up 10 per cent of Egypt’s 85 million, feel helpless. They have been victims of violence over the past few months, including repeated attacks on churches.

Scenes from last year’s revolution of Christians protecting Muslims as the latter prayed were hailed around the world. However, relations between the two communities aren’t so cordial anymore, especially with the incident at Maspero on October 9 last year.

The clashes started when thousands of Copts — joined by sympathetic Muslim activists — demonstrated in front of the “Maspero” building, the headquarters of the state TV, against the destruction of a church near Aswan, allegedly by a mob incited by a mosque preacher.

The protests turned violent leaving about 27, mostly Christian, demonstrators dead. Fourteen of them were crushed under military armoured vehicles, and more than 300 others were injured. No clear official investigation has been conducted. While Human Rights Watch claimed the military used excessive force against the demonstration, facts remain few amid the rumours and speculations.

“It was the most violent incident since the January 2011 revolution, but until now every time there is an incident, nothing happens, no one is charged or arrested. Offenders have to pay for what they have done to the churches and to the Christians,” said Mina Girgis, a Coptic activist and one of the January 2011 revolutionists.

The military personnel, though, strongly denied using force against Christians or any other Egyptian citizen. At a press conference led by a member of Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF), they rebutted the allegations and stated, “The army serves the nation and its entire people, Copts and Muslims, equally.”

SCAF member Major General Adel Emara said that soldiers on duty on that day were not armed with live ammunition and did not use armoured vehicles to kill demonstrators. “If some demonstrators were hit by armoured vehicles then it was done unintentionally; it goes against the creed of the Armed Forces to hit anybody — even enemy soldiers — with the armoured vehicles,” Emara said. According to him, SCAF has ordered a committee to investigate the events.

Tensions between Christians and Muslims have increased since the uprising last year. Maspero was one more in the string of events, adding to the profound sense of insecurity and isolation the Coptic community endures.

Following the violence, allegedly more than 100,000 Christian families have emigrated. Some Copts who live abroad have called for international protection to Egypt’s Christian minority. Naguib Sawiris, a renowned Coptic businessman, told Al Arabiya that such pleas will only hurt the Coptic cause and that it is “un-Egyptian” to seek foreign assistance in the country’s domestic affairs. There were varied reactions towards these incidents from the Muslim citizens. Many of them said that such attacks were orchestrated by a third party — either the remnants of the old regime or those acting on foreign agenda to create sectarian strife so as to “divide and conquer”.

“Such events are meant to abort the revolution. We know Egypt is targeted by hidden players, domestic and foreign,” Mahoud Taalat, a retired teacher, told Weekend Review. Talaat termed such attacks a “dirty conspiracy”.

Similar explanations for the troubles in Egypt are often heard from the military ruling council, which came to power after toppling Mubarak last year. The council has been telling the people that most incidents are personal feuds escalating into religious violence. Brutal crackdowns, however, such as the one alleged at Maspero, have eroded public’s faith in the council. Polls have shown that there is a severe drop in the confidence of the people in the council, which was once celebrated by Egyptians as the guardian of the revolution, especially as to whether it will hand over power.

“The credit that the military received from the people in Tahrir Square just ran out,” presidential hopeful Ayman Nour said while commenting on Maspero’s events. “There is no partnership between us and the council now that the blood of our brothers stands between us.”

A deep-seated distrust

In an attempt to revamp its image internally and externally, the esteemed committee of military council and representatives of the Freedom and Justice party, political wing of Muslim Brotherhood, which won around 47 per cent of parliamentary seats, visited Pope Shenouda during Coptic Christmas celebrations last month.

Although some Christians, especially the younger generation, wanted the pope to be revolutionary, the church followed the long-established protocol of welcoming representatives of the state. Some had blamed the pope for not allowing the Coptic youth to join the revolution in the early stages, but the pope clarified his stance in a statement saying, “Our youth are generally peaceful and are not attracted to demonstrations. Also at the start of the revolution, things were not clear. It later proved to be a free and non-violent movement. Many Copts joined it and many were martyred and wounded. Some newspapers published names of 12 of those Coptic martyrs and the church did not object to their participation.”

Relations between the Egyptian church and the rulers have always been a complex and sensitive issue. The Coptic Orthodox Church is regarded as one of the Oriental Orthodox churches. It accounts for about 90 per cent of Coptic Orthodox Christians in Egypt and abroad, besides being the Mother Church of both the Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox Churches.

According to ancient traditions, Christianity was introduced to Egyptians by St Mark in Alexandria, shortly after the ascension of Christ at around AD42 and it became the dominant religion in Egypt from the 4th-6th centuries, until the Arabs arrived and Islam took its place in the 7th century.

Mina Morad, a member of the Maspero Youth Union, said a knowledge of their histories is crucial to understanding the relations between political authorities and the church. “Although officially independent, the Copts’ reality of coexistence and second-class status thus continued to persist into the modern era: Coptic Church has been always influenced by the ruling system with a direct line to the Egyptian leaders,” Morad said.

The Egyptian church enjoyed a degree of independence, as Egyptian law gives non-Muslims the right to be governed by their own religious legislation in matters of personal status, which includes marriage, divorce and inheritance.

After being sent into exile in president Anwar Sadat’s era, Pope Shenouda had good relations with his sucessor, Mubarak. “I cannot deny that we had good relations with president Mubarak as a person. That’s why I see it as a personal obligation of loyalty not to mention bad points but rather remember the good ones. The problems we suffered were mainly due to those surrounding him,” the pope said. Meanwhile, Copts, the Middle East’s biggest Christian community, have voiced their concern about Egypt’s political future. Christians are worried about the first elected parliament, dominated by the Muslim Brotherhood, the 84-year-old group. The ultraconservative Islamists won the next largest share of seats, about 25 per cent.

Father Filopater Gameel, a Coptic priest, a leading member of the Maspero Youth Union and an eyewitness to the Maspero massacre, had this to say. “I am not surprised that the Islamists won the parliament majority. There were many hints in recent months that they were going to easily win many seats. That they were insisting the elections take place while all the other political forces were pleading that the elections be postponed indicates that both the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafists made a deal with the military council.”

Stronger statements were made by some Coptic intellectuals, including Milad Hanna, who warned that Copts, himself included, would embark on collective emigration from Egypt if the Muslim Brotherhood ascended to power.

Despite facing criticism, Hanna stuck to his words, which were published by Al Arabi newspaper: “I have sensed the state of anxiety after the results of the recent elections, as if Egypt was going to turn into a theocracy in a matter of weeks,” he said, adding that the Copts fear that they could become “second-class citizens” under the Brotherhood.

The peacemakers

Optimistic voices, on the other hand, such as those of prominent Coptic businessman Tharwat Bassily, wanted to give the Brotherhood a chance.

“I think it is too early to judge either how the Islamists will rule or how the Copts will react. We have heard a lot of theoretical arguments from them, but we still need to see what they will do practically. If they ensure that the parliament and its laws remain balanced and representative of the different factions of the Egyptian people, then that is great,” Bassily said. “However, if they give every law a religious twist, then that is not OK.” Traditionally, the church and its head, Pope Shenouda, don’t get involved in politics, focusing instead on the social aspects of the community. However, the present situation has pushed priests to encourage Copts to vote as a bloc to secure a minimum representation in the parliament.

To counter the Muslim Brotherhood, some clerics encouraged their parishioners to vote for the secular Egyptian Bloc, made up of both Muslim and Christian candidates. The Egyptian Bloc, newly founded by Christian business tycoon Sawiris, is a mix of mainly three parties: neo-liberal Free Egyptians, the socialist Gathering Party and the Egyptian Socialist Democrats. There are smaller Coptic parties, but for many Copts, a separation of religion and government is in their interests both as Egyptians and as Christians to defend themselves against the potential introduction of Islam into politics.

“We picked the Egyptian Bloc because it’s the most liberal group and because they are against religious parties, including the Muslim Brotherhood,” Father Ishak, a priest at St Mark’s, said. “And if elections are free and fair, it will mean that Copts are more clearly represented and be more active in building a new Egypt.”

Despite smear campaigns from Islamists’ parties, the Egyptian Bloc did manage roughly 8.9 per cent of all votes and 33 seats out of the 332 in the parliament.

Amid all political hassles, ordinary Egyptians on the streets don’t feel any of the tension. Mahmoud Al Shinawy, 35-year-old engineer, said that, on the streets, one can’t tell the two communities apart. “We stand next to our Christian brothers in the crowded metros, we suffer together the same crisis and hard living. We are one,” Al Shinawy said.

Raghda El Halawany