‘Weep, O weep, O Walsingham, / whose dayes are nights:

‘Weep, O weep, O Walsingham, / whose dayes are nights:

Blessings turned to blasphemies, / Holy deeds to despites;

Sinne is where our Ladye sate; / Heven turned is to helle:

Satan sitthe where our Lord did swaye - / Walsingham O farewell.

English folk ballad, attributed to Philip Howard (1557-1595)

What is the ‘real’ England?

This is not Walsingham, the great shrine of our Most Holy Lady the Theotokos.This lament for the blasphemous destruction of England’s Nazareth, however, is also a lament for the sack of all England’s shrines and monasteries between 1536 and 1541 - at the hands of a power-crazed king and his nobles who introduced … a foreign faith. More than that, it is a lament for the death of Merrie Olde Englande: the England not only of maypoles and Morris dancing but of saints and shrines, holy wells and above all monasteries, such as this, the Monastery of St. Mary and St. Ethelburga, on which we now stand. As the holy house of Walsingham was restored in 1931, so the Parish Church of St. Margaret and the Curfew Gate of this monastery still remain: tokens of an old England buried beneath the rubble of the so-called Reformation. As Fr. Alexander Haig of the Orthodox parish of St. Helen in Colchester writes, ‘both the Church and the Gate eloquently stand today, and, together with the ruins (uncovered in the twentieth century), remind us of a different world, where Holy Church still was bound up with ordinary, everyday life and brought everyday life into the environs of the Kingdom of Heaven’. A different world indeed: far removed from the empty walls of a gutted ‘Reformed’ church, far from the dark Satanic mills, the stiff, icy faces of the England built on its ruins. Here, on the site of Barking Abbey, we see the vestiges of the real England. Our pilgrimage today is an act of remembering – and repenting.

I have no drop of English blood. I am ‘English’ only in the language that I am speaking now and the land in which I reside and shepherd my flock. The saints of Barking, however, are no less my saints. They ‘belong’ no less to me than to any native of Essex; and, as a priest of the Orthodox Church, a hundred times moreto me than to a certain right-wing political party, often associated with Barking and Dagenham, whose soul is branded with the swastika. The saints of Barking intercede for all of us who have settled here in London, whether our roots lie in Cyprus or Ukraine, Greece or Russia, Serbia or Romania and the other lands that traditionally have held the holy Orthodox faith. Our earthly roots differ; our heavenly roots are the same. We celebrate the saints of Barking Abbey not because they are ‘White English’ – a category that would have made no sense to them – but because they are Orthodox saints of this place. They sanctify this soil not by planting the Union Jack or the flag of Saint George but the Cross of Christ.

By coming here today, we entrust ourselves to the prayers of our father among the saints, Bishop Erkenwald; to our holy mothers, Ethelburga and Tortgith, Hildelith and Wulfrida; above all, to our Most Holy Lady, the Theotokos and Ever-Virgin Mary, whose ‘Dowry’ England was, and is, and ever shall be in the world without end. By remembering the saints of Barking, we entrust the land and allits peoples to her care – just as the saints of Barking did and do. We help her, bit by bit, step by step, to restore the real England.

By the prayers of the saints of Barking, I have begun to restore the real England in my parish. A year ago, when I invited my congregation to take part in this pilgrimage, I received ‘hate mail’ of a sort from a disgruntled parishioner. Branding me a ‘cosmopolite’ and an ‘itinerant intellectual’, he insisted that the real England was akin to Protestant investment bankers rather than Orthodox nuns. By decrying the sacrileges of the so-called Reformation; by warning against the dangers of an insular, in-bred church; by calling upon the English people to return to the international faith of the saints of Barking, allegedly I had ‘insulted’ everyone born in these islands. I asked myself: had Saint Erkenwald, the true light of London, founded a church for ‘indigenous White English’ only? Did Saints Ethelburga and Tortgith reject the nun Hildelith when she came over from France? Through the mercies of God, this man and his wife soon after left my parish. The timing was anything but coincidental. Since then, ‘real’ Londoners of every hue and accent have filled our ranks. Devout Orthodox and enquirers from Bulgaria, St. Vincent, Iran, Poland, the United States, and far-flung corners of the earth have gathered under my care, united only in the true Orthodox faith.

It is to them that I dedicate my words today. If we would know the history of Barking Abbey, let us not lose ourselves in dates and events. Let us come to know holy persons who, as monks and nuns, belonged to no ‘nation-state’ but the Kingdom of God and its icon, the Orthodox Church.

Kingdom of the East Saxons

The year is 666. The place is Estseaxa, now called Essex. The North Sea borders it to the east, the River Stour divides it from the lands of the Sudfulc or ‘southern people’, now Suffolk, and from the Nordfulc or ‘northern people’, now called Norfolk. With what is now Cambridgeshire, these neighbours to the north make up the Kingdom of the East Angles, a pagan people from Denmark. Estseaxa itself, with Midelsexe and part of Hertefordscire (Hertfordshire) and Sudrie (Surrey), make up the Kingdom of the East Saxons, another pagan people originally from part of what is now Germany. The King of Estseaxa is Sighere, whose wife Osythis soon to establish a monastery at Chich on the River Colne, flowing out into the North Sea. The King of Midelsexe is Sæbbi,his brother, whose frequent prayer and almsgiving will elevate him to a glorified saint. The capital of his kingdom is the old Roman city of Lundonia (London), at the lowest point where the River Thames can be bridged.

Near the village of Barking, about eight miles from the capital and isolated in the marshy lands between the River Roding and the Thames, an Orthodox abbot builds a monastery for his sister. He builds it out of wood and thatch, not in the marsh but near the Thames in contact with London. His sister is the nun Æthelburh or Ethelburga, meaning ‘noble fortress’. Her brother’s name, meaning ‘truly brave’, is Eorcenwald.

Erkenwald is an East Anglian nobleman, possibly of royal blood. As an East Angle, he comes of a people recently converted to the Christian faith. Only in the last years of the previous century did Gregory the Dialogist, Pope of Rome and author of our Divine Liturgy of Presanctified Gifts, send Bishop Augustine to convert the Germanic pagans on the far frontier islands of the historic Roman Empire. Only sixty years ago, Bishop Mellitusbegan preaching to the East Saxons. The task of converting them, taken up by Bishop Cedd from the north, is still underway when Abbot Erkenwald builds his monastery.

Already abbot of a small men’s monastery on the isle of Chertsey in the Thames, Erkenwald is intent on creating a ‘double monastery’ where the monks and the nuns live separately, under the spiritual rule of his sister Ethelburga. On land probably belonging to his family, Erkenwald soon becomes spiritual father of the community while Abbess Ethelburga governs its affairs. The earliest years of the new monastery, however, are a small part of much wider events in the Church. Only three or four years after it is created, a ‘cosmopolite’ and an ‘itinerant intellectual’ arrives on the North Sea coast who will change the lives of the East Saxons forever.

The new Archbishop of Cantuaria, or Canterbury, is named Theodoros, ‘the gift of God’. He is a native of Tarsus in Cilicia and a hierarch of the patriarchal see of Antioch. A cultivated Roman from the cosmopolitan, Greek-speaking East, the new Archbishop is anything but provincial. Refugee from the Muslims, he has lived in Athens, old Rome, and the imperial capitol of Constantinople. He sets himself a task: to unite the disparate churches and monasteries, first of the East Saxons, then of the Angles, into one ecclesial province to correspond to the former Roman province of Britannia. The age of tribal kings is over. To achieve his goal, Archbishop Theodore elevates Erkenwald to the rank of Bishop of London in 675 – only nine years after he has founded the abbey at Barking. Bishop Erkenwald is destined to outlive his sister and attain a ripe old age, dying in 693 in the abbey that he himself founded.

Archbishop Theodore’s goal of unity comes at an opportune time. While Western Europe is still divided among the Germanic peoples who overran it beginning in the fifth century, the Roman Empire survives in the East – but only barely. In the year that Erkenwald founds Barking Abbey, Emperor Constans II tries in vain to shift his imperial court from Constantinople to Italy only to meet resistance from the Lombards. His motive? An aggressive new faith called Islamencroaches, year by year, toward the imperial capital. Theodore of Tarsus is one of many cultured East Romans in search of a new start in the West. By directing the newly-consecrated Erkenwald to bring the churches of Britain into unity, he restores the real Roman Empire:not the city of old Rome but the Roman faith, that is, the Orthodox faith.

The Golden Age of Barking

Abbess Ethelburga, sister of Erkenwald, does not govern Barking alone. Her friend Theorgirtha, or Tortgith, is the mistress of novices. In the early years of the monastery, she suffers a paralysis that lasts six whole years. Unable to move or speak, she becomes a visionary. Shortly before the abbess falls asleep, Sister Tortgith sees a vision of her body wrapped in light and drawn up into the heavens by cords brighter than gold. Tortgith will have another vision of Mother Ethelburga, speaking to her and encouraging her, before she herself falls asleep in faith.

The second abbess, Hildelida or Hildelith, is a Saxon princess who took her monastic vows in a women’s monastery at Chelles-sur-Seine near Paris. More experienced than Ethelburga, she has taught both Ethelburga and Tortgith the monastic life. For more than thirty years as abbess, she develops Barking into a great centre of learning and piety. Firm, self-disciplined, yet very gentle, she wins the respect of the scholar Adhelm and corresponds with Boniface, the missionary to the so-called ‘Old Saxons’of Frisia and northern Germany. The ‘New’ Saxons under Hildelith are no provincial barbarians. They are well-read in Latin, the Greek Fathers, rhetoric, and the science of the day. Among the nuns trained under Hildelith at Barking are Cuthburga and Cwenburga, both sisters of King Ine of Westseaxa,or Wessex, who later found the monastery at Wimborne, in eastern Dorsete, or Dorset.

The golden age of Barking ends in 870. Marauding Danes,the last ferocious Germanic pagans, sack and pillage Britain from York to Kent. Huddled together in the wooden structures, the nuns of Barking are burned alive when the Danes set the monastery on fire. For an entire century, the monastery lies in ruins. While Emperor Basil I, founder of the Macedonian dynasty, campaigns against the Muslims and codifies the Roman law in the East, England is plunged into the Dark Ages. By the grace of God, the candle that Erkenwald and Ethelburga lit refuses to go out.

Wulfhilda and the Growth of Feudalism

A century has passed. The year is 970. A brilliant general of Armenian stock, John I Tzimiscês, sits on the imperial throne in Constantinople. He rules over a splendid court, a well-trained army, and a treasury enriched by imported goods from Italy to Mesopotamia. In England, King Eadgar, later called ‘the Peaceable’, has united the Kingdoms of Northumbria and Mercia to his native House of Wessex. With the Archbishop of Canterbury, a noble from Wessex named Dunstan, he restores the monastery at Barking. Now it is a women’s monastery, following the international Rule of St. Benedict. The abbess is Wulfhilda, a talented and beautiful nun whom King Edgar himself once had in mind for a bride. Like her predecessor Hildelith in centuries past, she is also firm in her vocation. It is said that she fled the king through the sewers! The times, however, are very different from those of Ethelburga and Hildelith. Kings increasingly lay claims on churches and monasteries, rejecting Christian standards and echoing the ancient, pagan Germanic concept of Heil: the divine power that flows directly from the chieftain. In this spirit, upon King Edgar’s death, his widow Ælfthryth or Elfrida ejects Abbess Wulfrida in order to retire to Barking in her later years. Four years later, the widowed Queen arranges the murder of her stepson, Edward the Martyr, at Corfe Castle in Dorset. Only upon her death, Abbess Wulfrida returns from Dorset to take the reins at Barking once more. She falls asleep in 1000, when many in England and elsewhere expect the world to end.

The world does not end in the year 1000. A world ends. The brutal Emperor Basil II,nicknamed Voulgaroktónos or the ‘Bulgar-slayer’ for his conquest of the Bulgarians in the Balkans, rules in an era of decline. Caught in a web of wars between Normans in Italy and Seljuk Turks advancing into Anatolia, the Roman Empire sinks into endless intrigues that merit the insult ‘Byzantine’. In northern France, relatives of the same Normans who threaten the Orthodox provinces of southern Italy now threaten England. In 1066, William the Bastard defeats the last Saxon King, Harold II Godwinsonat Senlac Hill, eight miles north of the town of Hastings. For some four and a half centuries, England is divided between a French-speaking nobility and an English-speaking Saxon underclass. The new King William spends several months at Barking Abbey, while Saxon and other workers build his new castle that is to become the Tower of London. His legacy to the abbey is much darker.

From the continent, the Normans introduce a new system of rule called feudalism, rooted in the Germanic military culture that these descendents of the Danes share with the Franks, Goths, and other Germanic peoples. Under the new feudal rule, the Abbess of Barking holds the dignity of a ‘baron’ – if not the political powers – and therefore receives from the king extensive lands in the counties of Essex, Middlesex, Surrey, Buckinghamshire, and Bedfordshire. In exchange? Feudal Norman kings reserve the right to appoint abbesses. Usually, they find this a convenient method of rewarding or disposing of female relatives. The wives of Kings Stephen and Henry I, as well as the daughters of Kings Henry II and John, all become abbesses of Barking. Each one of them, incidentally, bears the typically Norman name of Maud. Henry II even appoints Mary Beckett, sister of Archbishop Thomas Beckett, atoning for his murder. Ironically, Thomas Beckett died in defence of the rights of the Church (now Latin, that is, Roman Catholic) against the claims of the state and its power-hungry princes.

The shadow of the last undeniably Orthodox abbess, Wulfhild, falls over this feudal period in the history of Barking that began sixty-six years after she fell asleep. The monastery’s rise in wealth and decline in a free voice in its own affairs foreshadow the greatest catastrophe of all.

The Catastrophe

The year is 1436. Two young boys, Edmund and Owen Tudor, spend four years under the care of the abbess of Barking while their mother, Catherine of Valois, becomes a nun at the abbey in Bermondsey. Edmund, later First Earl of Richmond and father of the future King Henry VII, is unlikely to imagine that his own grandson would desecrate his childhood home. For him and his son, indeed his grandson Henry VIII, Barking is no less the real England than Walsingham. It is the key to England’s spiritual past, more vital to England’s identity than any new ideologies and ideas imported from continental Europe. Ironically, in the interests of cutting England off from continental Europe, the holy Monastery of St. Mary and St. Ethelburga will disappear.

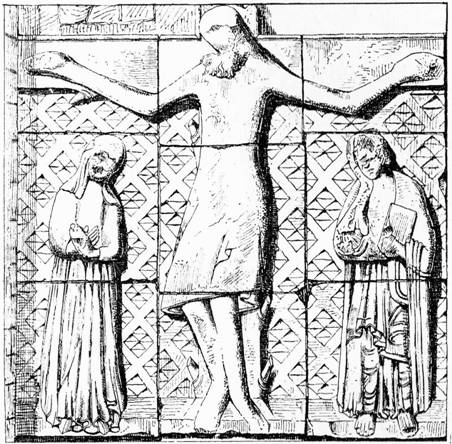

The year is 1540. Enacting the hateful Suppression of Religious Houses Act 1539, the monastery is forcibly dissolved. The last abbess, Dorothy Barley, is pensioned off. Most of the nuns simply return to the homes that they occupied before: hardly martyrs but confessors, who suffer not for the Orthodox faith but the faith in monastic life. In one year, 552 monasteries and related houses are dissolved. (The act that destroyed Barking was not fully repealed until the Statute Law Act of 1989!) What happens to the household of the nuns? All jewels, gold plate, and silver plate go to the king’s jewel house. Lead stripped from the roof covers the king’s palace in Greenwich. Stone from the walls goes partly to Kent, to build the king’s new palace in Dartford. The rest is open to plunder. Since natural stone is rare in Essex, the vultures fly in for the kill. The abbey that stood for almost nine hundred years is stripped to the ground. Only the local parish church and the old Curfew Gate, with its upstairs chapel and the Holy Rood depicting the Crucifixion, remain. Barking itself is crucified.

Aftermath

I am not a historian of Anglo-Saxon England. I am only a theological scholar. Please direct your questions about the history of Barking to my better informed brothers and sisters in the faith; and if in any detail I have erred, may the saints of Barking intercede for me, the sinner. I can only ask the question that arises in my prayers when I walk on this hallowed ground.

What does the name Barking mean to the average resident of Britain, indeed of London, in 2012? In 2006, the British National Party became the second party on the local Barking and Dagenham council. Four years later, its leader Nick Griffin came third in the Barking constituency but the party itself lost all of its twelve councillors in the borough. I at least have eyes to see the prayers of Saint Erkenwald and Saint Ethelburga at work. Beset by financial woes, the one political party most explicitly dedicated to ridding Britain of its ‘immigrant problem’ has promised to cut all federal funding to ‘non-indigenous’ faiths. Compared to East Finchley, where I live, Barking seems to have few trees to sustain the indigenous faith of the Druids. The sight of Muslim faces, and the faces of Christians of Jamaican, Barbadian, and Sub-Saharan African descent, may worry some locals who remember the all-white culture that came before. Seldom do they consider that this ‘indigenous’ culture of ‘Anglo-Saxon Protestants’ was itself built in recent centuries on the ruins of the abbey where we stand. Do they consider? We who confess Christ, not the indigenous’ gods such as Woden and Thor; we, whose diocesan bishops hail from Syria, Cyprus, Russia and many other ‘non-indigenous’ lands – we Orthodox, too, are a minority in Britain. We are unknown, exotic, mysterious, and at least a bit threatening to the ‘indigenous’ people of these islands. A minority. For the time being.

For us, the members of the same Church that Saints Erkenwald, Sebbi, Cedd and Mellitus, and King Edward the Martyr belonged to; the Orthodox Church that Saints Ethelburga, Tortgith, Hildelith, Wulfrida, Cuthburga, Cwenburga, and Osyth sanctified by a simple nun’s prayer; the Church that flourished in this land since one of those ‘olive-skinned immigrants’, Theodore of Tarsus, raised the Anglian monk Eorcenwald to the rank of bishop – for us, the real England is in the flattened, broken stones intersecting the green grass. It is in the prayers of the saints who once walked here and of the Most Holy Virgin Theotokos, who looks lovingly on England, her Dowry, and longs to hold it in her arms again. It is in our Orthodox people, who come here from every corner of the globe, united today in the prayer that England someday will return to what she once was and still is in the eyes of Almighty God: a province of the Orthodox Church.

Through the prayers of thy Most Holy Mother and of all the Saints of Barking, Lord Jesus Christ our God, have mercy upon us and save us. Amen.

Barking Abbey, 12 May 2012

Saint Epiphanius of Constantia

Saint Ethelhard of Canterbury

© Reverend Father Alexander Tefft, Ph.D.

All rights reserved.